Related Posts

YOGA TO REGULATE THE AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

Related PostsYoga,...

IS ALCOHOL A HEALTH FOOD? ALCOHOL AND YOUR HEART

Related PostsWelcome to...

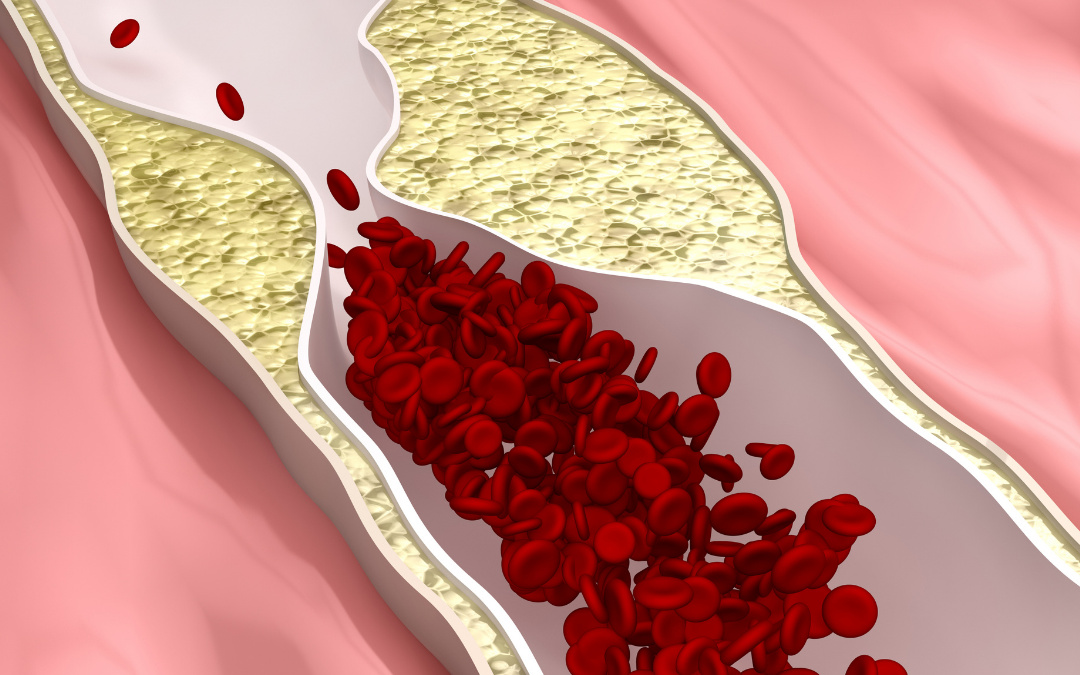

METABOLIC DYSFUNCTION AND THE ATHEROGENIC LIPID PROFILE

Related PostsWelcome to...

THIS IS YOUR HEART WITH METABOLIC DYSFUNCTION

Related PostsWelcome to...

METABOLIC HEALTH IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN WEIGHT LOSS

Related PostsWelcome to...

ARE YOU DEFICIENT IN OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS?

Related PostsRecently,...

WILL FISH OIL HELP OR HURT YOUR HEART?

Related PostsOmega-3...

GRAINS: HEALTH FOOD OR POISON?

Related PostsGrains are...

A TURN TOWARD NATURE TO SOLVE THE “PROBLEMS” WITH MEAT

Related PostsWhat’s up...

EARLY ABLATION FOR ATRIAL FIBRILLATION: IS IT BETTER THAN LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS?

Related PostsIn my...

THE FUTURE OF PLAQUE IMAGING & DIAGNOSING CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Related PostsWhat is...

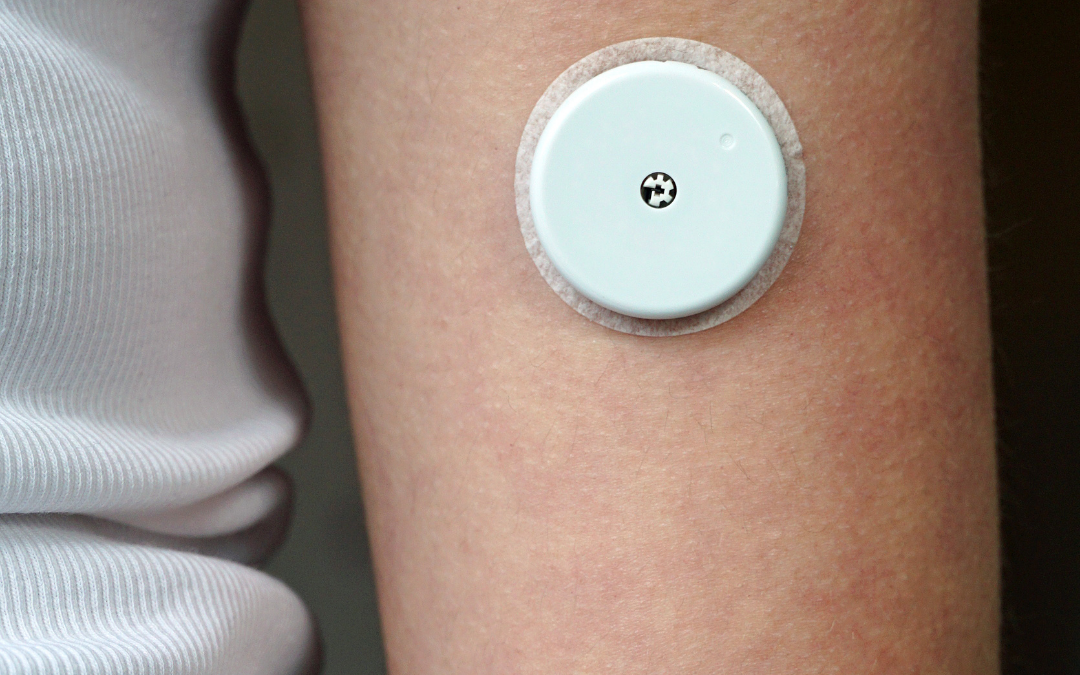

SHOULD YOU WEAR A CONTINUOUS GLUCOSE MONITOR?

Related Posts Many of...

FASTING SAFELY AND SUCCESSFULLY WITH DIABETES

Related Posts Almost...

THE “SAD” AMERICAN DIET

Related Posts What is...

MYTHS & TRUTHS ABOUT WOMEN AND FASTING

Related Posts Patients...

HEART DISEASE IS DIFFERENT IN WOMEN

Related PostsThe...

THE 6 KEYS TO FASTING SAFELY WITH HEART DISEASE

Related PostsIf you...

IS YOUR GUT THE CAUSE OF YOUR HEART DISEASE?

Related PostsAt...

BENEFITS OF INCREASING YOUR MUSCLE MASS

Related PostsYou may...

ABLATION AND BEYOND FOR ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

Related PostsShould...

PASS THE SALT

Salt is in the news again: “Landmark study shows simple salt swap could prevent millions of deaths each year.”

We can’t live without salt. It is true that many people need less salt, but some people need more. Those who need less either have a very high intake (remember, processed foods are very high in salt), or because they are salt sensitive. Being salt-sensitive is something you can, and should, fix.

The “landmark study” that calls for across-the-board reduction in salt intake was published in the August 2021 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine and is titled “Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death.” 21,000 people from rural villages in China participated for this study. Participants all had a history of stroke or were over 60 years old and had hypertension. They were randomized to either consume the same salt intake as they normally would (the control group) or to use a salt substitute that contained salt (sodium chloride) with potassium chloride. Strokes in the people on normal salt intake occurred at a rate 0.33% per year but in only 0.29% of people using the salt substitute.

This may seem like a small effect on stroke risk for any given person, but multiplied over millions of people, the difference in stroke occurrence adds up.

How much salt is too much?

What we call salt is made of sodium chloride (NaCl) and comes in many forms: sea salt, kosher salt, table salt. You likely have at least one kind in your kitchen. This study, and typically when we talk about salt, we’re really talking about sodium, which makes up 40% of salt. In three grams of salt, there’s just over 1 gram of sodium. Different kinds of salts weigh more (table salt is 6 grams, kosher salt is 3 grams) and thus have more sodium.

In the study, the average sodium intake was around 4 grams per day in the control group. This is a pretty typical amount of salt intake on average, but salt intake varies a lot from person to person.

People who consume a diet heavily dependent on processed foods can easily ingest 6 to 12 grams of sodium per day. This level is commonly agreed to be unhealthy. Diets high in processed foods are also low in potassium.

Advocates of a low-salt diet suggest that 1.6 grams of sodium is best for optimal health. This is a significant salt restriction compared to salt usage nearly everywhere.

There is a good argument to make that a less restrictive amount of salt in the diet, around 3 grams of sodium, may be optimal. Not to mention more doable.

Can you get too little salt?

Low-salt diets can cause mild dehydration. So the problem with significant salt restriction is that your body will compensate for that dehydration with counter-regulatory hormones like adrenaline and angiotensin. This will maintain blood pressure at the expense of damaging artery linings and activating your immune system. A low-salt diet that causes mild dehydration can be an additional source of chronic stress. Subclinical dehydration can explain why blood pressure falls in some people who increase their salt intake.

Several studies have demonstrated a U-shaped curve relating sodium intake, with both mortality and cardiac events being higher in both low- and high-salt intake groups, and a sweet spot around the 3 gram level.

But determining the appropriate amount of salt in the diet for any given individual is a little more complicated. Some people are “salt sensitive” and others are not. Only salt sensitive people have a rise in blood pressure when dietary salt is increased moderately.

Salt sensitive people are the ones who most need to be concerned about their salt intake. Salt sensitivity causes your kidneys to reabsorb more of the sodium from filtered blood and return it to your bloodstream. The added sodium brings more water into the blood to rebalance, and the increased volume of blood increases your blood pressure. The temporary increase in sodium concentration from eating can also cause constriction of your arteries until the effect is diluted with water intake.

What causes salt sensitivity?

People can be salt sensitive because of medications or because of genetic variants that cause them to retain more of the salt that they eat. Most often, people are salt sensitive because their insulin levels are too high. Insulin signals the kidneys to retain sodium.

You can deal with salt sensitivity by reducing your salt intake, but more effectively, you can deal with salt sensitivity by improving your insulin resistance with a whole food diet, lower carbohydrate intake, appropriate exercise, and even time-restricted feeding and fasting. Improving insulin resistance also helps your body retain potassium. Improving salt sensitivity with diet improves health overall; a low-salt diet just covers up issues with salt and insulin.

The people in this latest salt study were likely salt sensitive on average because they all had either a stroke or hypertension. They were likely to benefit from lower salt intake and increased potassium intake, but that does not mean that everyone needs to be on a low salt diet.

It is important to understand that the results of a clinical trial only apply to people very much like the people in the clinical trial.

What to do about your salt intake

Do you know, or suspect, that you might be salt sensitive? Here are some steps you can take to reduce your sensitivity and risk.

- Cut out ultra-processed foods

Whether you are salt sensitive or not, one of the best things anyone can do for better health is to reduce or eliminate highly processed foods from their diet. This is a gigantic task; 60% of the calories consumed in the US come from high-sodium processed foods, which also contain high levels of sugar and additives.

- Increase your potassium

If you have healthy kidneys: increase your potassium intake by eating leafy green vegetables and well-sourced meats. Salt substitutes that contain potassium chloride, as used in the study above, can also be used to increase potassium intake.

- Increase your magnesium

Many people are deficient in magnesium, which helps reduce salt sensitivity and helps our muscles and heart function. Increase your magnesium with leafy greens, nuts, and seeds.

- Improve insulin resistance

Visceral fat, high glucose levels, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, or elevated blood pressure are signs of metabolic syndrome that result from high insulin and insulin resistance. There are effective dietary treatments for elevated insulin and metabolic syndrome. In addition to cutting out ultra-processed foods, increase your exercise and consider fasting, which is known to improve insulin resistance. Check out our upcoming monthly community fast here.

- Try medication to reduce salt retention

There are occasions when changing to medications like aldosterone blockers can reduce salt retention that’s caused by genetic variants or other blood pressure medications. An intake of 3000–5000 milligrams per day may be best if you are not salt sensitive. This amounts to 7.5-12.5 grams of table salt per day, which equals 1.5-2.5 teaspoons per day.

- Make sure you’re getting enough salt

If you have a healthy, whole foods-based diet, without processed foods, it is easy to be inadvertently low in your salt intake because there isn’t much salt in vegetables and healthy fats. In that case, make sure to salt your food to taste and let your body tell you how much you need. You can use an app like Cronometer to measure how much salt you are getting from your diet. Compensate for increased salt loss when exercising in the heat or using a sauna with 1-3 extra grams of sodium.

Fasting and salt

Fasting is another time that you must pay attention to your salt intake. If your insulin levels are high and you have a lot of salt retention, when you fast your insulin levels will drop and a lot of salt will be excreted in your urine. This exaggerates the dehydrating effects of fasting and often results in headache, weakness, and dizziness. Taking 1-2 tsp of salt per day when fasting is usually enough to keep hydrated, but some people may need more. Take less salt if you have swelling, congestive heart failure, or kidney disease. If you have any of these conditions you really should fast with the guidance of your doctor. Read more about fasting with diabetes.

If you eat salty food, dilute the effects by drinking water with it.

Public health versus personalized care

People researching or writing about public health tend to make sweeping recommendations about salt intake because so many people consume far too much processed food or have metabolic syndrome induced salt sensitivity.

Public health, while vital in many ways, is different from personalized medicine. A personalized approach is better for addressing most lifestyle-based health issues, especially if you’ve already cut out processed foods. Salt sensitivity and insulin resistance can be treated with the right knowledge and a whole-foods approach.

Learn more: watch our recent webinar “Do You Need to Reduce Your Salt?”